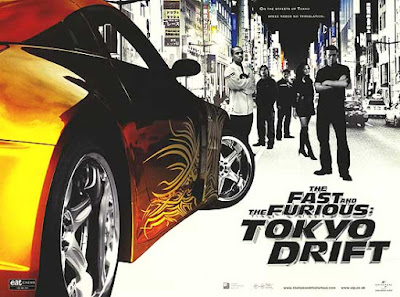

What at first glance may seem like nothing but a series of loud and brash car-racing action flicks, the Fast and the Furious series is in truth a little unparalleled in modern film history. Over the course of seven different movies the franchise has successfully reinvented itself- starting out as a fairly small-scale street racing franchise and slowly transforming into a series of action blockbusters played out on a gigantic scale, continually daring themselves to get bigger and bigger. This reinvention was a process, one led by the combination of the star power of Vin Diesel and Dwayne Johnson, but what really makes the franchise stand out is its treatment of its central characters as an ethnically diverse “family” unit, a team made up of people serving different narrative purposes and functions, a group who love and care for each other like siblings. While Fast Five was the film which set the standard for the action franchise it has become, the third film, The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift, acts as the pinnacle of what a modern street-racing movie can be. Serving as a formal, stylistic, and thematic reinvigoration of the overall series, while also paying homage to the themes set up by the previous two pictures,Tokyo Drift pointed the series in the direction it eventually went down.

For the film, the producers chose Asian-American director Justin Lin, who had previously only directed one film, 2002’s Better Luck Tomorrow, about a group of Asian-American high school seniors who begin dipping into criminal activities. Where the first Fast entry was a Point Break-esque narrative with street racing and the second was a Miami-set buddy cop movie, Tokyo Drift is centered upon high school student Sean, played by Lucas Black. From the opening credits, Lin drops the viewer into a highly-stylized world full of color and movement, one in which street racing isn’t just a pastime, but a way of life. Colliding with a group of football players, their vibrant purple and yellow letterman jackets popping off the screen, Sean challenges Clay, a jock, to a street race. This is where Lin’s aesthetic shines through- taking place at a housing development, the bright colors of the cars zoom across the screen as the camera moves both adjacent to and against the movement, all the while Kid Rock’s “Bawitdaba” functions as the soundtrack. Eventually, after much destruction, both cars end up crashing, and Sean is sent to Tokyo to avoid facing criminal charges.

With Tokyo Drift, Justin Lin merges the high school criminal world setting of Better Luck Tomorrow with the street racing of the previous two Fast and the Furious entries. Entering into a high school in Tokyo, Sean is introduced by military brat Twinkie to Tokyo car racing, an underground world populated by young drivers. His first night, Sean races D.K., the “drift king”, in an act of arrogance, totaling driver Han Lue’s car and landing himself in even bigger trouble. Owing him money, Sean is taken under Han’s wing, and Han teaches him the art of “drifting”, a specific way of driving popular on twisting mountain ranges and in parking garages. Here, drifting is portrayed not just as a form of street racing but as an art unto itself. It’s something which must be studied carefully, practiced, and mastered. Lin heavily stylizes the act, the swift movement of the car romanticized through color and light. In one scene, one of the more gorgeous moments of the franchise, Sean’s romantic interest Neela takes him out drifting in the rural Japanese mountains. Throughout the whole scene, the color is deep blue, and the soundtrack is ethereal as the couple soar and twist their way through the winding roads. Tokyo Drift is the Fast entry with the single most car racing, as its sequels moved more towards action-oriented storytelling; good, then, that it works so well here, as the racing is constantly and consistently formally inventive and stylized.

Narratively, Lin’s decision to set the film within a high school allows for him to subvert certain previously-established narrative roles. The characters aren’t fully-grown adults but rather kids playing around within an adult world. D.K.’s uncle may be Yakuza, but D.K. is just a volatile and insecure young driver. Neela, the romantic interest, a girl without a family, is caught-up within the criminal world, but at the same time she’s a high school student in the center of a love triangle. Sean is positioned as the hero but is still just a kid escaping legal trouble by living with his father, whom he has a strained relationship with. The franchise’s addition of Han Leu, too, is one of its smartest- Han is effortlessly cool, philosophical, and in control. He doesn’t drift unless he has a specific reason to, and no petty rivalry is enough to convince him. Han is a character with a history, he’s come to Tokyo to escape his past, and to Han Tokyo represents the quasi-Wild West of the modern world; a place of lawless freedom, and unlimited profit.

Narratively, Lin’s decision to set the film within a high school allows for him to subvert certain previously-established narrative roles. The characters aren’t fully-grown adults but rather kids playing around within an adult world. D.K.’s uncle may be Yakuza, but D.K. is just a volatile and insecure young driver. Neela, the romantic interest, a girl without a family, is caught-up within the criminal world, but at the same time she’s a high school student in the center of a love triangle. Sean is positioned as the hero but is still just a kid escaping legal trouble by living with his father, whom he has a strained relationship with. The franchise’s addition of Han Leu, too, is one of its smartest- Han is effortlessly cool, philosophical, and in control. He doesn’t drift unless he has a specific reason to, and no petty rivalry is enough to convince him. Han is a character with a history, he’s come to Tokyo to escape his past, and to Han Tokyo represents the quasi-Wild West of the modern world; a place of lawless freedom, and unlimited profit.

Lin’s playing around with character and heightening of the intimacy and style of drifting is matched by his technical, formal proficiency. During the day, Tokyo is stripped of bright colors, save for the bright, flashy yellow, green, and orange paint of the sports cars. At night, however, Tokyo is turned into a living, breathing, romantic car-racing utopia, an urban underworld of neon-lit signs and fluorescent light bulbs. The film has a distinctly 2000’s feel throughout, with its camera movements and soundtrack featuring Kid Rock and the Teriyaki Boyz. Unlike any of the other films, the action is limited- where the other films would feature gunfights or action setpieces this film has street races and montages. Tokyo Drift’s most stunning sequence involves a car race through downtown Tokyo at night; D.K. chasing down Han as Sean attempts to catch up to them. Lin strips away the soundtrack for a single shot of the car widely drifting through a dense crowd in a brightly-lit square. It's peak action filmmaking, the camera staying stationary for the shot and then immediately cutting, moving with the action, bringing the viewer deeper into the scene. In this way, <I>Tokyo Drift</I> is the franchise’s answer to the auteur theory- strip away the well-known characters, heighten the accent of the main character, incorporate a diverse, interesting cast, and stylize the racing scenes- all the while placing the narrative within a setting the director is known for and comfortable with. Justin Lin’s ability to take what was a fairly lackluster franchise and reinvigorate it, making it all his own, is a stunning accomplishment.

"I wonder if you know, how they live in Tokyo."